We Finally Have A New Govt After 61 Years. How Did Other Nations Do After Theirs Changed?

We're actually doing pretty good.

Barisan Nasional (BN), the world's longest ruling coalition, was voted out in the historical 14th General Election (GE14) 40 days ago

Former premier Datuk Seri Najib Razak addressed the media after Barisan Nasional's loss in GE14.

Image via Asian Correspondent"We accept the verdict of the people and (BN) is committed to respect the principles of parliament and democracy," Najib was quoted as saying by Asian Correspondent.

Pakatan Harapan eventually took over Putrajaya by winning 116 seats in comparison to BN's 79 in the Parliament. This contrasts BN's 140 parliamentary seats in 2008 and 133 seats in 2013.

As of last week, BN is down to 59 seats after all four component parties of Sarawak BN announced their decision to leave the coalition.

Malaysia experienced an unprecedented wave of reforms under the Pakatan Harapan government since GE14, joining countries that experienced successful regime changes

Apart from the historic appointments of Malaysia's first female Deputy Prime Minister and a Sikh federal minister, the promise to abolish "draconian laws" such as the Anti-Fake News law is also in the process of being fulfilled, among other campaign pledges.

While it serves as a strong warning to dominant one-party regimes in Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam), Pakatan Harapan's win is the latest addition to nations that are transitioning to democratic rule after the fall of a regime.

Our neighbours Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines went through democratic transitions as well. How did they fare after that?

1. Indonesia: the fall of Suharto in 1998

Former president Muhammad Suharto, who was in office for three decades, resigned in 1998 following severe economic and political crises in Indonesia.

A Foreign Policy report credited the 1997 Asian financial crisis for the downfall of Suharto, where 80% of the Rupiah's value against the dollar was wiped out. This, coupled with the May 1998 riots, ultimately led to Suharto's resignation.

Since then, the transfer of power has been peaceful for the five presidents who came after the dictator. Furthermore, the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), created in 2003, went after shady politicians, judges, and public officials.

Nonetheless, government of the widely celebrated President Joko Widodo was reported by Human Rights Watch in 2017 as failing at implementing policy initiatives despite declaring his support for human rights. Religious minorities continue to suffer under the authorities, and people continue to be arrested and prosecuted under the country's blasphemy law.

2. Myanmar: Saffron Revolution 2007

In 2007, a string of economic and political protests were triggered by the military-run government, Tatmadaw's decision to remove subsidies on fuel prices. As a result, petrol and diesel prices immediately doubled, while the price of compressed natural gas increased by 500%.

This sparked protests led by students, political activists, and Buddhist monks in the form of nonviolent resistance. The movement was then dubbed "Saffron Revolution" – named after the saffron-coloured robes worn by Buddhist monks at the demonstrations.

The Tatmadaw eventually stepped aside in 2011 to allow the formation of a military-backed, civilian-led government. The pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest, while 200 political prisoners were freed as part of a wider amnesty.

In 2007, Buddhist monks marched under the watch of security forces in Yangon.

Image via The IrrawaddyNonetheless, New York Times reported last year that Myanmar's transition to democracy became something very different from what the world expected. Myanmar citizens expressed desire for a dictator-style leader, and think that democracy should be guided by religion and nationalism.

Furthermore, the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya, together with social controls against journalists and minorities, are still prevalent. Hence, there is still work to do.

"Myanmar's biggest threat is not the return of the dictatorship but an illiberal democracy," Thant Myint-U, a historian and former United Nations official, was quoted as saying by New York Times.

3. The Philippines: the fall of Marcos in 1986

Former president Ferdinand Marcos, who ruled the Philippines for 21 years, imposed martial law on the Philippines in 1972 and still managed to retain vast powers after lifting it in 1981. Under the martial law, he managed to overhaul the constitution, silenced the media, and violently oppressed his opposition. Furthermore, according to New York Times, Marcos and his wife, Imelda had hundreds of millions of dollars worth of real estate and antiques in New York alone.

However, New York Times reported that after the assassination of Benigno Aquino, a longtime opponent of Marcos, the regime faced a few potent threats: a shaken economy, opposition from the Roman Catholic Church, and the growth of the Communist insurgent movement.

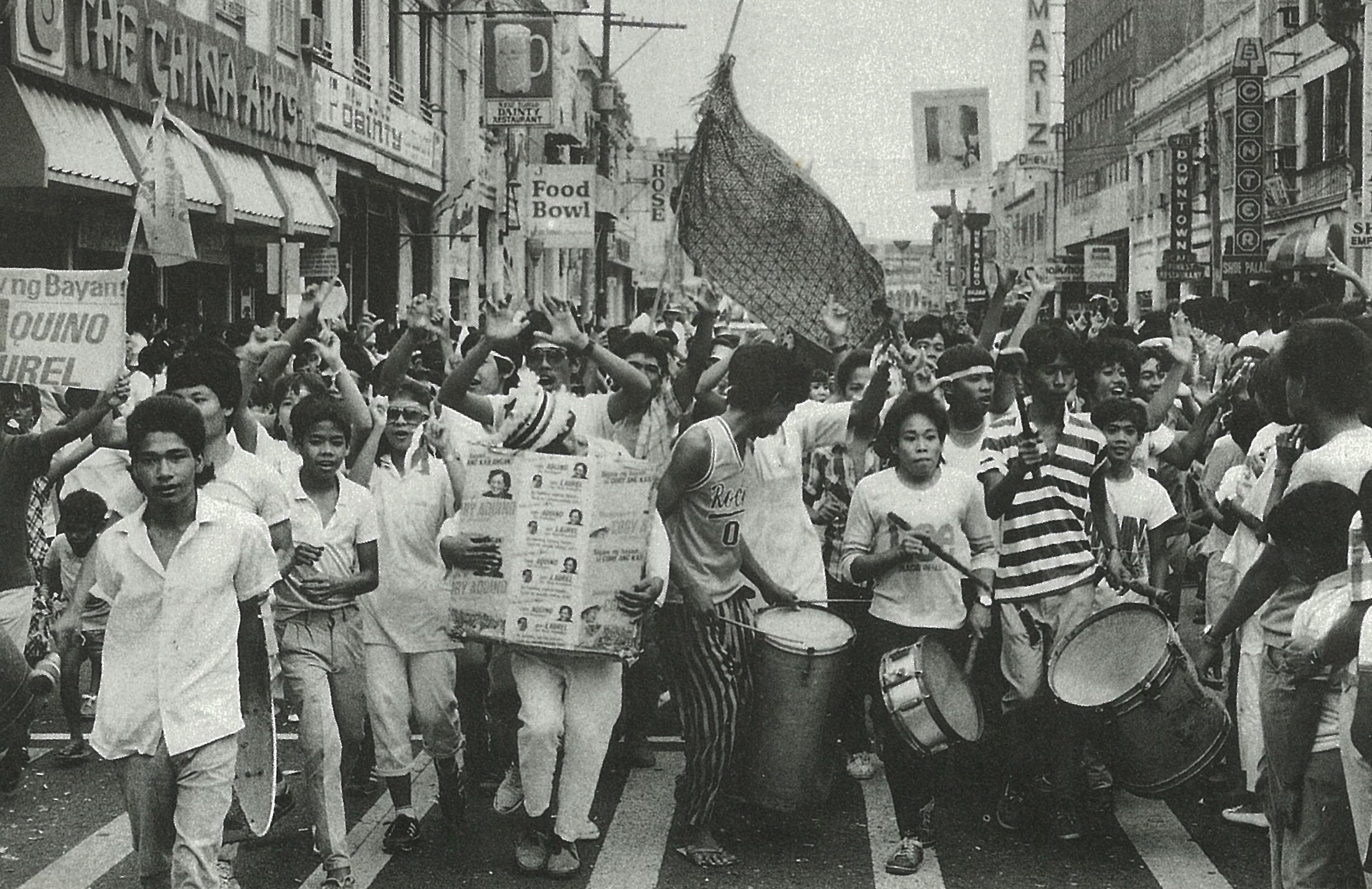

People marched during the People Power Revolution in 1986, also known as the EDSA Revolution.

Image via Philippine Canadian InquirerWeeks after Marcos was declared the winner in the 1986 election, two million Filipinos took to the streets to protest against decades of governance by the dictator. The three-day long demonstration was known as the People Power Revolution, or the Yellow Revolution due to the yellow ribbons used during the protests.

Eventually, the Marcos family fled the Philippines to the United States, while Aquino's widow, Corazon Aquino was installed as the new President following the revolution.

The Philippines' progress in transitioning to democracy is now halted by President Rodrigo Duterte, who pushed the country into its "worst human rights crisis" since the Marcos regime, according to Human Rights Watch.

Duterte's war on drugs has claimed an estimated 12,000 lives of mainly poor Filipino civilians since he took office in 2016. Nonetheless, his government has consistently denied reports of the death tolls as "alternative facts".

Against the backdrop of our neighbours, Malaysians managed to defy the trajectory of Asian democracies

After a flourishing of democracy in the region, Asian countries seem to be suffering from reversals of their transitions. Financial Times reported that surviving Asian democracies have been looking increasingly frail in the presence of rising authoritarianism and extremism.

The peaceful power transition in Malaysia therefore represents the "important swing of the pendulum" back to accountable democracy in Asia, according to The Diplomat. Malaysians will now watch the Pakatan Harapan government closely for electoral promises to be fulfilled.

Nonetheless, Malaysia's bloodless revolution remains good news for Asian countries that are experiencing creeping authoritarianism today.